Present in England from c.1050-1650 (photographed example, Westminster Abbey: constructed (c.1050-1090, additions made until 1745)

Located across the British Isles (photographed example, Westminster Abbey: located in Westminster, UK)

England is a realm well known to be a land rich in architectural treasures spanning from the Neolithic period (i.e. the illustrious Stonehenge in Wiltshire) to the progressive “green” skyscrapers of glass, steel, and concrete arising today from the City of London, the heart of UK business. The country is an assortment of differing architectural styles which changed and evolved throughout this long history. Westminster Abbey (pictured) has been deemed a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of the nation’s most prized cultural and architectural possessions and is a prominent example of the Gothic style popular in the Middle Ages through to the early Tudor period and which continued to be constructed until the early Stewart period.

History

GENESIS OF THE STYLE

The term “Gothic” was applied to this architecture style and culture by those who invented it to mean barbarous due to its status as non-classical. The style found its inception in France, specifically in Burgundy and Provence as a development from earlier styles of Western Christian architecture (labeled “Classical” or “Romanesque” (Bond 7)). The earlier and more classical styles of building took root from Ancient Greek and Roman architectural schools and featured grand spaces characterized by high, sweeping domes like that of the Pantheon in Rome and columns for support.

The construction of Romanesque churches or “basilicas,” however, was often hampered by a particularly difficult problem. “Romanesque architecture is the art of vaulting a basilica…with nave, aisle walls, lean-to roof, and clerestory wall containing windows. This was the problem of problems for Western builders from the ninth century onward; to vault an aisled church without destroying its clerestory lighting” (6). Structurally, this paved the way for stylistic alterations to solve this problem. One solution was what would become Gothic architecture.

This new school of building was essentially a fusion of several main elements: of diagonal ribs, pointed arches, and flying buttresses, which culminated in an extremely unique and recognizable style which commanded attention.

` These sharp, dynamic features which dutifully served a very practical and structural purpose also left congregations in awe and wonderment and the Gothic style spread out of France and across Europe Prolifically “In fits and starts, [the spread of Gothic architecture] continued for the next four hundred years throughout Europe. By the mid-fifteenth century, Gothic cathedrals could be found from Scandinavia in the north to the Iberian Peninsula in the south, and from Wales in the west to the far reaches of Eastern Europe” (Scott 11).

Gothic Architecture continued to progress in England and the thirteenth century led to the rise of the “Decorated English Style” around the reign of Edward the First. This new design featured heavy ornamentation which became almost omnipresent. Ornate designs could be found present wherever one looked, to the grand facades on the outside, to the smallest intricate details found on individual wall brackets.

Gothic Architecture continued to progress in England and the thirteenth century led to the rise of the “Decorated English Style” around the reign of Edward the First. This new design featured heavy ornamentation which became almost omnipresent. Ornate designs could be found present wherever one looked, to the grand facades on the outside, to the smallest intricate details found on individual wall brackets.

Toker, Franklin. “Gothic Architecture by Remote Control:

An illustrated BuildingContract of 1340.” Art, Bulletin 67, no.1 (March 1985):67. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed November 27, 2011)

IMAGES IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE

Westminster Abbey. Taken by author

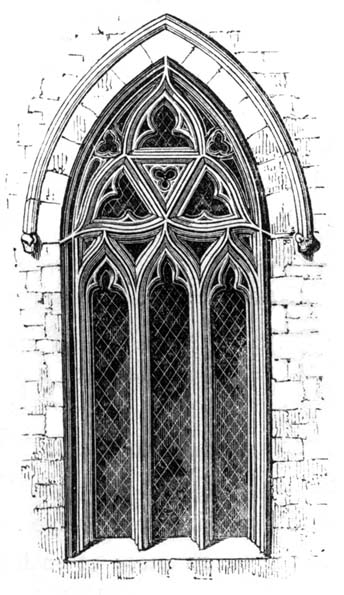

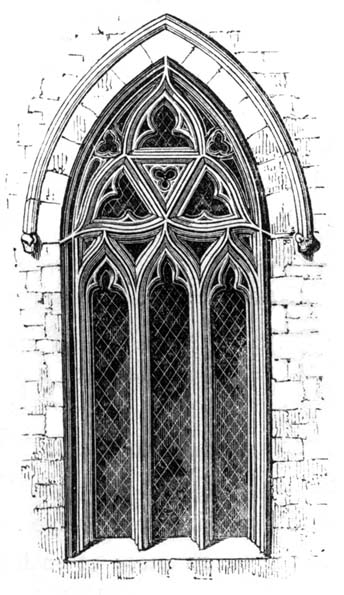

Window, Dunchurch Church, Warwickshire. Taken from The Principles of Gothic Ecclesiastical Architecture, Elucidated by Question and Answer, 4th ed

THE SPREAD TO ENGLAND

Romanesque/proto-Gothic structures were present in England before the Norman conquest of 1066, with the beginning of the construction of the first portion of Westminster Abbey in 1050 (Bond 14), however, with the advent of William the Conqueror’s invasion the land experienced a profound level of construction of churches in this style. “There was hardly one of the greater Anglo-Saxon churches which was not rebuilt and a great number of churches, entirely new, were erected” (Bond 14). This is a prime example of an immediate and long-lasting effect that the Norman Conquest of Britain had. Many of these places of worship were also grand in scale; much larger than their counterparts in the mother country. These are impressive facts, however, they are underscored even more by the fact that the entire land had a population of about half that of London in the present day (around four million).

The Romanesque/proto-Gothic explosion would continue in England for over a century, developing its own characteristics unique to the British Isles. Late in the 12th Century and early in the 13th century, however, the style transitioned into a fully Gothic model, starting with the larger cathedrals and buildings being constructed at the time, then filtering down to the smaller parishes and counties later on in the period.

FLOURISHING IN ENGLAND

Quite analogous to Darwin’s theory of Natural Selection and chance variation, as Gothic architecture evolved on the isolated island of Great Britain, English Gothic style differed from its continental counterpart. This led to a sense of “British-ness” and proto-national pride within the realm of England.

England | Length (ft) | Continent | Length (ft) |

Old St. Paul’s | 586 | Milan | 475 |

Winchester | 530 | Florence | 475 |

St. Albans | 520 | Amiens | 435 |

The table above indicates the emphasis on structural length of English Gothic cathedrals relative to continental cathedrals (Bond 49).

England | Internal Height (ft) | Continent | Internal Height (ft) |

Old St. Paul’s | 103 | Cologne | 155 |

Westminster | 103 | Beauvais | 150 |

York Choir | 102 | Bologna, S. Petronio | 150 |

The above table shows that English cathedrals fell short of those on the continent n internal height (Bond 50).

England | Area (sq. ft) | Continent | Length (sq. ft) |

Old St. Paul’s | 72,460 | Seville | 150,000 |

York | 63,800 | Milan | 92,600 |

Lincoln | 57,200 | Saragossa | 80,000 |

The continental cathedrals also were superior in area (Bond 50).

The specific “Anglo-Norman” style of truly Gothic architecture can trace its development to the reign of Edward the Confessor. His construction of what is now Westminster Abbey heralded truly the breakaway design which is deemed worthy of its own category (Bloxam). This style may be recognized by its semicircular arches, its massive piers, which are generally square or cylindrical, and from numerous ornamental details and moldings which are specific to the style.

Gothic Architecture continued to progress in England and the thirteenth century led to the rise of the “Decorated English Style” around the reign of Edward the First. This new design featured heavy ornamentation which became almost omnipresent. Ornate designs could be found present wherever one looked, to the grand facades on the outside, to the smallest intricate details found on individual wall brackets.

Gothic Architecture continued to progress in England and the thirteenth century led to the rise of the “Decorated English Style” around the reign of Edward the First. This new design featured heavy ornamentation which became almost omnipresent. Ornate designs could be found present wherever one looked, to the grand facades on the outside, to the smallest intricate details found on individual wall brackets.Decorated English Style prevailed throughout the next century and was followed by developments during the reign of Edward the Third (c.1375) which can be grouped and referred to as “Perpendicular (or Florid) English Style” (Bloxam). Like the preceding style, the Florid or Perpendicular style was heavy in ornamentation, however, it differed in that the “beautiful, flowing contours” of the Decorated style were superseded by direct vertical and horizontal lines of division and angular edges (Bloxam). This style, enjoying prominence until the middle of the sixteenth century may also be seen as the climax or turning point in the history of Gothic architecture in England.

It was after roughly a century and-a-half of the predominance of the Perpendicular style within the British Isles that the final incarnation of the English Gothic form of architecture took hold. This form, known as the “Debased Style” was, nevertheless far inferior in design compared to its illustrious and ornate predecessors. Emerging into existence around 1540 in the later years of the distinguished reign of Henry VIII, Debased style was stylistically more simple and inauspicious. The name “Debased” itself arises from “the general inferiority of design compared with the style it succeeded, from the meagre and clumsy execution of sculptured and other ornamental work, from the intermixture of detail founded on an entirely different school of art, and the consequent subversion of the purity of style” (Bloxam). As explored below in the “Gothic Architecture and the Reformation” section of this entry, the decline of the Gothic style in England is closely linked to the changed brought about by Henry during the Protestant Reformation.

Though the art and construction of the Gothic style fell into decline at about this time, a revival of interest and intrigue into the art of Gothic architecture took off in England around two centuries later in the 18th and 19th centuries. This “Gothic Revival” style, as it is known, spread throughout Europe and into North America well into the 20th century.

Stylistic features

Though Gothic style within England progressed, changed, evolved, and devolved within the course of around six centuries, as enumerated above, English Gothic style can be described generally as, in essence, a culmination or fusion of several key elements. These elements were mainly a result of the constructional challenges to the erection of churches that the Romanesque and Classical styles posed to architects and builders. Plainly, the major characteristics shared by buildings constructed in the English Gothic style are pointed arches, diagonal ribs, and flying buttresses.

· Pointed Arches: Perhaps the most noticeable exterior feature of Gothic cathedrals and other structures is the pointed arch. Though there are a myriad of different types of pointed arches that have been employed in Gothic construction (such as the “obtuse” and “Tudor” arches), pointed arches can be found on any surviving Gothic cathedral. The vault of Gothic cathedrals is impossible without this shape and it is, therefore, ubiquitous and essential to the structure. (Toker 187)

· Diagonal Ribs: Similar in shape to the pointed arches, these diagonal ribs were used on the ceilings of Gothic cathedrals, generally above the aisles. Like the pointed arch, its shape is essential to vaulting the structure. (Toker 190)

· Flying Buttresses: This exterior design feature encompasses the angular shape of both the pointed arch and diagonal rib. The primary purpose of the flying buttress was to support the exterior facades of the structure.

Gothic Architecture and the Reformation

Henry’s Reformation of the Church and the establishment of Anglican Church, of which he appointed himself the premier, unintentionally and quite accidentally had profound implications for the history of Gothic Architecture, specifically its downfall. On the eve of this unprecedented and immense religious, social and political change, England’s landscape was unparalleled in the number of religious edifices of sheer variety of style collected across the ages. “Next to the magnificent cathedrals, the venerable monasteries and collegiate establishments, which had been founded and sumptuously endowed in every part of the kingdom, might most justly claim the preeminence; and many of the churches belonging to them were deservedly held in admiration for their grandeur and architectural elegance of design” (Bloxam).

Perhaps the largest contributing factor to the downfall of this most interesting school of architecture which had endured for so long was the dissolution of the monasteries. The responsibility of building, rebuilding, and decorating the existing monasteries which had been built over the course of several centuries (which often proved costly with such lofty and intricate designs) had been defrayed out of the monastic revenues and private donations historically. However, when the crown seized these, the construction and upkeep of these historically precious facilities declined and many fell into ruin (Bloxam).

Much of the Protestant and Puritan contempt toward the Catholic Church lay in its emphasis on ornamentation. Gothic style, as detailed earlier, is characterized by an extreme attention to detail and contained ubiquitous elaborations (Farahbakhsh 184). As the Protestant wave became dominant within the country, reformers, in addition to cutting down on the ornamental practices and rituals of the Church, also curbed any further excessive decoration on new churches. Additionally, as the older structures crumbled, they were renovated in less stylistic fashion. “Parochial churches were, therefore, now repaired when fallen into a state of dilapidation, in a plain and inelegant mode, in complete variance with the richness and display observable in the style just preceding this event” (Bloxam).

In the stead of the Gothic style, more classical design originating from Italy began to predominate during the 16th century and by the reign of Charles I little remained of the Gothic.

Bibliography

Bloxam, Matthew. The Principles of Gothic Ecclesiastical Architecture, Elucidated by Question and Answer, 4th ed.. Oxford, UK: 2006. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/19737/19737-h/19737-h.htm

Bond, Francis. Gothic Architecture in England. Hallandale, FL: New World Book Manufacturing Company, 1972.

Farahbakhsh, Alireza. "Social Protest Through Architecture: Ruskin's "The Nature of Gothic" as an Embodiment of His Artistic and Social Views." Midwest Quarterly 52, no. 2 (Winter2011 2011): 182-199. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed November 28, 2011).

Hawkins, John. An History of the Origin and Establishment of Gothic. London, UK: S. Gosnel, http://books.google.com/books?id=iKAaAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=gothic architecture history&hl=en&ei=j43RToWcIcLg0gGfoNn0Dw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDoQ6AEwAQ

Scott, Robert. The Gothic Enterprise: A Guide to Understanding the Medieval Cathedral. London, UK: University of California Press, 2005.

Toker, Franklin. “Gothic Architecture by Remote Control:

An illustrated BuildingContract of 1340.” Art, Bulletin 67, no.1 (March 1985):67. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed November 27, 2011)

IMAGES IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE

Westminster Abbey. Taken by author

Window, Dunchurch Church, Warwickshire. Taken from The Principles of Gothic Ecclesiastical Architecture, Elucidated by Question and Answer, 4th ed

No comments:

Post a Comment