Fulling Wool

by: Elizabeth Jensen

Scottish Waulking Wool

The main material for clothing in the Tudor period was wool. Although fabrics such as linen and silk were available, they were expensive and rare except among the highest classes. Wool was the most commonly worn by the people, especially in the lower classes. They were not permitted to wear any type of materials such as fur or velvet. The processing of wool began far into Medieval Times where it was most lucrative from the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries.

Wealth was measured by the amount of sheep you owned and England’s countryside from the Lake District, West County, southern Downs, and East Anglia were covered with flocks. During Tudor times, Lavenham, one of the smallest towns in England was one of the wealthiest. Many regulations were set up early own to monitor the trade of wool out of the country. Taxes were placed on sacks and barrels of wool starting with Edward I. Great revenues were gained from the importance of wool in England. During Elizabeth’s reign commoners all people except for nobles were required to wear woolen caps to church on Sundays to show support to the wool industry.

Wool was a very important part of England’s economy and although it was a high export especially in cities like London it stayed mostly within the country. It was not until the late fifteenth century that the abundance of wool far surpassed England’s need and export trade began to really take off. “The late Middle Ages saw a major shift in the composition and hence destination of England’s export trade. She started out as a supplier of raw materials- cereals, wool, and to a lesser extent metals and leather. By the sixteenth century, the export of these items had declined relatively, and in the case of cereals absolutely, and cloth had become the major export of England.” There were also new developments in Spanish trade throughout Europe and its effects on English profit.

The process of developing wool grew significantly throughout England’s time. During the twelfth century the process of manufacturing wool was done by hand and foot. With the use of a fulling trough the wool would be submerged originally in stale urine which later turned to fresh clean water. A Fuller would then crush the wool by foot (much like crushing grapes), and it was then beaten or rung out by hand. This was necessary because sheep’s wool contains oil called Lanolin. This process was also called tucking the wool. “Tucking is the old word for “fulling,” which is the process whereby wool is scoured, beaten, and cleansed of the lanolin grease with which sheep make themselves warm and waterproof. “ This process was necessary to take the loosely woven wool and work it into a tightly-knit cloth product.

Later developments led to the creation of fulling mills. These mills were highly populated in rural countryside’s where streams and rivers were most abundant. The use of water created the power to drive the mills. They were most important to cut the demanding labor out of fulling wool. They consisted of two large wooden beams that would beat the wool while it was submerged in boiling hot liquid. This process would clean and soften the wool more evenly. The rapid rhythmic beating also helped prevent damage to the wool while a person slowly turned it throughout the trough. The finished product would be flat rounded piece of wool that would then be laid out onto tenter-planks for drying.

The production of sheep and farming changed significantly throughout England. Before the Black Plague farmers relied on open range grazing but with the decline in population and land use, England turned to utilizing the land in enclosed farms. This changed the productivity of the sheep industry. “The enclosure process for sheep farming made life easier, both for farmer and his sheep.” This new way of farming sheep is thought to have in some ways led to loss of value of English wool. Wool was valued by its length and softness. At this time in the late 1400- to early 1500’s English wool was long and thick which did not produce lightweight comfortable clothing. At this time the rise in quality of Spanish wool rose to outstanding levels. A woolen jacket made from English wool would weigh about four pounds compared to the Spanish one pound jacket. This was not good for the English market. Other factors, such as a high demand of wool in England also played a decline, especially in English foreign trade. There was a high price demand for wool in the foreign market but a significant decline in the demand for English woolen goods by the late 1500’s.

Art and culture were very elaborate and popular forms of expression during the Tudor period. Many forms of expressing one’s self were done through what you wore and how extravagant your clothing was. From Henry VIII to Elizabeth I laws were in place to separate the classes by their clothing, regardless of how wealthy you were. To break these laws could result in loss of title, land, and for some imprisonment or death.

The Sumptuary laws, designed by King Henry VIII laid the ground rules for dress among the classes for the next hundred years. A persons social standing and how they dress was a major importance during the Tudor reign. They were broken down the by the class and what each stage of nobility could or could not wear. At times these laws were strictly enforced and a major part of everyday English life, but as time grew on their significance began to dwindle and fade out.

During this time a great indicator was not only what type of fabric you wore and how you wore it, but also the colors that your fabric was dyed. The poor commoners of the England wore basic tan or off white loose fitting woolen clothing. Men wore basic Trousers and a tunic and women in dresses down to their ankles always with an apron. Their clothing was never elaborate or held any eye catching color. The most often wore colors worn by the upper class were blue, red, and brown. The most expensive was the brightest red and the blackest black.

Fabric dyers in this time were very highly paid but the worst of company. To get a rich blue color a dyer would use the Woad plant. This plant is from the cabbage family and has a very potent stench when boiled down. Queen Elizabeth I herself proclaimed that she would not be less than five miles from any woad dyer, ever. These men were often hermits and always had the stench on them as well as their dyed blue hands. It is known as one of the worst jobs in history.

The history and art of wool has been inexistence since before Medieval Times. Some historians can trace it back to the Persian conquests. The process has been developed throughout the years and only continues to grow and become more refined. For the early years of the Tudor period wool was a vital part of life and its process only began to grow throughout their time. A fulling through is only one stepping stone into the inventions and manufacturing of wool that continues to be developed on today.

Scottish Waulking Wool

This is an example of early 17th century Scottish women fulling wool. Unlike the trough that I focus on this has ripples in it that work much like a wash board does today. This is a modern take on an late medieval fulling trough.

Blocking Wool- Fulling Mill

This process of fulling wool is more modern into the early-middle Tudor period. Here the wool is placed into the trough along with the boiling liquid and is beaten by the wooden planks as the worker slowly turns it along. The mill is being powered by a a local stream or river.

Division of Classes Through Clothing

This is an example of the Tudor Sumptuary Laws. You can see the lay out of what could and could not be worn by people from the commoner to the highest of royalty.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. The Modern World-System I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. London: Universtiy of California Press, 2011.

Winchester, Simon. The Map that Changed the World: William Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology. New York: HarperCollins, 2009.

Bowden, P.J. "Wool Supply and the Woollen Industry." The Economic History Review. 9. no. 1 (1956): 45.

Bowden, P.J. "Wool Supply and the Woollen Industry." The Economic History Review. 9. no. 1 (1956): 48.

The Richmond Museum of English History

Monday, November 28, 2011

The John of Gaunt Window

by Debbi Price

Created in the 15th century

The John of Gaunt window was a part of Agecroft Hall, a 15th century Tudor-style mansion originally located on the banks of Lancashire’s Irwell River in England. This beautiful window first adorned the private chapel of the mansion. Later, the home was remodeled and the chapel space became the dining room. Today, one can visit this grand window in Richmond, Virginia, in the United States of America.

How did an authentic Tudor mansion end up in Richmond? In 1925, a wealthy man named Thomas C. Williams purchased the dilapidated Agecroft Hall. The house was dismantled and shipped to Richmond, Virginia where it was reassembled overlooking the James River.

According to the wall placard, the John of Gaunt Window was not part of this original shipment of 1925. According to Agecroft Hall staffers, it was kept in the family and instead moved to Lovell’s Court in Dorset, England, approximately 200 miles south of its original home. The window was finally reunited with Agecroft Hall in the summer of 1979. Unfortunately, many of the glass panels broke and extensive restoration needed. The repairs were completed in 2009 and it is currently showcased as one of the Hall’s permanent exhibits.

It is not known when the window panels and the hefty carved oak frame they sit in were originally made however; it couldn’t have been before the reign of Henry VII, unless the panels were installed at separate times. It is also not known who the artisan or artisans that made the John of Gaunt might have been, but later in the third section I will tell you a little information about the typical glass painters of the time.

It is not known when the window panels and the hefty carved oak frame they sit in were originally made however; it couldn’t have been before the reign of Henry VII, unless the panels were installed at separate times. It is also not known who the artisan or artisans that made the John of Gaunt might have been, but later in the third section I will tell you a little information about the typical glass painters of the time.

While the design is simple, not nearly as ornate as many stained glass windows created during the same time period, the most fascinating aspect of the window panels are the stories and politics one finds associated with the images. Much of the secular population was illiterate and it became popular to use coats of arms and banners to signify ones familial and political associations. Let’s take a closer look at the individual panels and see how they relate to people and politics.

Please continue to my website for a more in-depth look at the John of Gaunt window, including a panel by panel explication of the elements of the window, an obscure legend surrounding its history, and a look at the glass artisans of the time period. A bibliography of resources consulted in my research of the window is also included.

Created in the 15th century

The John of Gaunt window was a part of Agecroft Hall, a 15th century Tudor-style mansion originally located on the banks of Lancashire’s Irwell River in England. This beautiful window first adorned the private chapel of the mansion. Later, the home was remodeled and the chapel space became the dining room. Today, one can visit this grand window in Richmond, Virginia, in the United States of America.

How did an authentic Tudor mansion end up in Richmond? In 1925, a wealthy man named Thomas C. Williams purchased the dilapidated Agecroft Hall. The house was dismantled and shipped to Richmond, Virginia where it was reassembled overlooking the James River.

According to the wall placard, the John of Gaunt Window was not part of this original shipment of 1925. According to Agecroft Hall staffers, it was kept in the family and instead moved to Lovell’s Court in Dorset, England, approximately 200 miles south of its original home. The window was finally reunited with Agecroft Hall in the summer of 1979. Unfortunately, many of the glass panels broke and extensive restoration needed. The repairs were completed in 2009 and it is currently showcased as one of the Hall’s permanent exhibits.

It is not known when the window panels and the hefty carved oak frame they sit in were originally made however; it couldn’t have been before the reign of Henry VII, unless the panels were installed at separate times. It is also not known who the artisan or artisans that made the John of Gaunt might have been, but later in the third section I will tell you a little information about the typical glass painters of the time.

It is not known when the window panels and the hefty carved oak frame they sit in were originally made however; it couldn’t have been before the reign of Henry VII, unless the panels were installed at separate times. It is also not known who the artisan or artisans that made the John of Gaunt might have been, but later in the third section I will tell you a little information about the typical glass painters of the time. While the design is simple, not nearly as ornate as many stained glass windows created during the same time period, the most fascinating aspect of the window panels are the stories and politics one finds associated with the images. Much of the secular population was illiterate and it became popular to use coats of arms and banners to signify ones familial and political associations. Let’s take a closer look at the individual panels and see how they relate to people and politics.

Please continue to my website for a more in-depth look at the John of Gaunt window, including a panel by panel explication of the elements of the window, an obscure legend surrounding its history, and a look at the glass artisans of the time period. A bibliography of resources consulted in my research of the window is also included.

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Agecroft Hall

Welcome to the historical Agecroft Hall! Agecroft Hall a former Tudor estate that was previously located in England. This historical place is currently located in the heart of Virginia’s capital, Richmond. However before you can completely understand the significance of Agecroft Hall, you must understand the history behind it. In order to comprehend any thing or anyone, it is always beneficial to research the history.

Let’s take it back a little more than 500 years ago to 1485 in England. During this time the Tudors were in power throughout England. The Tudors were “A Welsh-English family that ruled England from 1485 to 1603. Henry Tudor was the son of Margaret Beaufort, who was descended from King Edward III through an illegitimate line, and Edmund Tudor, the son of Princess Catherine of Valois and her second husband, Owen Tudor.” (Hanson 1)

As you can see, the Tudor family was an extremely large dynasty that was reining England. The Tudor family line goes on for years and years. “Through Catherine of Valois, Jasper was the half-brother of the last Lancastrian king, Henry VI. The Yorkist branch of the Plantagenet dynasty would eventually seize the throne from the incompetent Henry VI, but their reign ended when Richard III was killed at the battle of Bosworth Field on 22 August 1485. Henry Tudor then claimed the throne as King Henry VII. He promptly married Elizabeth of York, daughter of the only successful Yorkist king, Edward IV, and niece of Richard III. Henry VII and Elizabeth of York's second son, three of their grandchildren and one of their great-grandchildren, would rule England as part of the Tudor dynasty. When their rule ended, the throne passed to the Scottish branch of their family - James I was the great-grandson of their daughter, Margaret Tudor.” (Hanson 1)

By understanding the Tudor history and rulers, it will allow you to visualize the state that England was in starting in the 1480s. Throughout the beginning years pertaining to Agecroft Hall, Henry VII (also called Henry Tudor) was ruling England. He ruled from 1485 to 1509. During this time England was in a state of change and reinventing itself. “Henry VII's first task was to secure his position. In 1486 he married Elizabeth of York, eldest daughter of Edward IV, thus uniting the Houses of York and Lancaster.” (The British Monarchy 1) Henry VII wanted to bring the York and Lancaster families together in order to bring unity and also to avoid any battles that could occur between them. This may be looked at as a smart war tactic on Henry VII’s behalf.

After Henry VII died in 1509, his son Henry VIII took over the throne of England. Henry VIII ruled from the years of 1509 to 1547. He is considered to be a different kind of ruler than his father was.

“From his father, Henry VIII inherited a stable realm with the monarch's finances in healthy surplus - on his accession, Parliament had not been summoned for supplies for five years. Henry's varied interests and lack of application to government business and administration increased the influence of Thomas Wolsey, an Ipswich butcher's son, who became Lord Chancellor in 1515.” (The British Monarchy 1)

One of Henry VIII’s main focuses while he was ruling was England’s foreign policy agreements with the surrounding countries. He wanted to create stable and beneficial foreign policy relations with these countries to secure the safety of England.

“Henry's interest in foreign policy was focused on Western Europe, which was a shifting pattern of alliances centered round the kings of Spain and France, and the Holy Roman Emperor. (Henry was related by marriage to all three - his wife Catherine was Ferdinand of Aragon's daughter, his sister Mary married Louis XII of France in 1514, and the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V was Catherine's nephew.)” (The British Monarchy 1)

Henry VIII reign consisted of several other events that would forever change the way that England, during that time, was run. One of the biggest events that took place during his reign was the Protestant Reformation. The way that the Protestant Reformation began is a very common event that most people can remember easily. It began in 1517 when a man named, “Martin Luther, a German Augustinian monk, posted 95 theses on the church door in the university town of Wittenberg. That act was common academic practice of the day and served as an invitation to debate. Luther’s propositions challenged some portions of Roman Catholic doctrine and a number of specific practices.” (Protestant Reformation 1)

During this time in England, and majority of Europe, questioning the church had not been done. Luther’s accusations toward the church were surprising for this society to see and experience. Some of the specific accusations and problems that Luther wanted to vocalize for the church and people to hear was, “that the Bible, not the Pope, was the central means to discern God’s word — a view that was certain to raise eyebrows in Rome. Further, Luther maintained that justification (salvation) was granted by faith alone; good works and the sacraments were not necessary in order to be saved.” (Protestant Reformation 1)

“Luther had been especially appalled by a common church practice of the day, the selling of indulgences. These papal documents were sold to penitents and promised them the remission of their sins. To Luther and other critics it appeared that salvation was for sale. Rome enthusiastically supported the use of indulgences as a means to raise money for a massive church project, the construction of St. Peter’s basilica.” (Protestant Reformation 1)

In relation to Henry VIII, the Reformation was the time period that most associate with him wanting to get a divorce. During this time Henry VIII was married to Katherine of Aragon. He was so determined to make this happen that he would stop at nothing to get what he wanted. Henry VIII was turned down by the Pope several times, but that did not deter him from what he wanted; a divorce.

Most people would wonder why Henry VIII wanted a divorce so badly from Katherine of Aragon. It would appear that she was a horrid wife because of Henry VIII’s persistence to be free of her. The actual reason why Henry VIII wanted the Pope to grant him a divorce from Katherine of Aragon is because he desperately wanted a male heir to the throne. He wanted his own child to be the one to take over after his death. Katherine of Aragon tried to give him a son, but the few times she was pregnant it with a boy, they soon passed away. Katherine of Aragon was only able to give Henry VIII a baby girl, Mary, who was born in 1516. She would later on be known as Mary Tudor and sometimes even called Bloody Mary.

Since the Pope would not grant Henry VIII a divorce from his wife, he decided to take matters into his own hands. “In the end, he simply declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England and confiscated all church lands and money in his country. This is known to history as 'the dissolution of the monasteries.' However, Henry VIII remained a spiritual Catholic; he disliked Luther's ideas and was never a Protestant himself. He simply rejected Roman Catholic influence in England.” (Hanson 1)

After Henry VIII opened up the door of challenging the church and believing in other religions, this trend continued throughout history long after his death in January of 1547. “The influence of the Roman Catholic Church in England declined while the new ideas of the Reformation began to slowly gain adherents. The resulting religious convulsions would consume most of Europe for the entire century. In Tudor England, the conflict between the old faith and the new consumed its rulers. Henry VIII was a lapsed Catholic; his successor Edward VI was a devout Protestant; his successor Mary I was a devout Catholic; her successor Elizabeth I was, understandably enough, a religious pragmatist.” (Hanson 1)

Now that the historical, political and social background of England during the 15th and 16th century is clear, it will be much easier to understand the importance of great Agecroft Hall estate. This historical estate directly ties in to the history of England.

As stated earlier, Agecroft Hall is a historical Tudor estate. It was originally built in 1485, which is in the late 15th century. “The original name of the house was Edgecroft, as the house sat on the edge of a field, or croft.” (Waddelove 1) The name was soon after changed to Agecroft Hall.

This historic estate was originally built in Lancashire, England; which is close in proximity to the city of Manchester. (Lancashire is about 200-300 miles from London). Agecroft Hall’s “primary residents were the Langley and the Dauntesey families, wealthy members of the gentry just a step below nobility on the social ladder.” (Elvgren 1)

The Langley and the Dauntesey families were prestigious families during this time. Most people are unaware of how these two families are connected throughout history. “When Sir Robert Langley died in 1561 his estates were divided between his four daughters. He left Agecroft and the adjacent lands to his daughter Anne, who married William Dauntesey.” (The Agecroft Collection 1)

Anne and her husband William Dauntesey owned Agecroft Hall for years to come. Then, Agecroft Hall was passed down throughout the Dauntesey family. “The hall began to deteriorate during the 1800s. Following the discovery and mining of coal near the house, the placement of railroad tracks through the grounds and finally a fire in 1894, Agecroft Hall was abandoned and remained unoccupied from 1910 until 1925.” (Elvgren 1)

After remaining unoccupied for 15 years, Thomas C. Williams Jr. then purchased Agecroft Hall. Williams, a Virginia businessman, bought this historic estate at an auction. A man named Henry Morse, an architect, was the one who actually sought out and bought Agecroft on Williams’ behalf. During this time Williams was a client of Morse. “An American buying what was, basically, a piece of English history raised quite the uproar in England, all the way to Parliament. However, in the end, everyone came to realize the gift Williams was giving this roughly five hundred year old manor.” (Visit Agecroft Hall 1)

Being that Williams lived in Virginia, it was only natural that he would have wanted to have his newly purchased property in Virginia with him. However due to the fact that this was a large property, most would have thought that this was not at all possible. The businessman in Williams led him to ultimately do the unthinkable.

“Morse arranged for Agecroft Hall to be carefully dismantled, crated, and shipped across the Atlantic to Norfolk, Virginia. From there the crates traveled by train to Richmond where Morse hired contractors to put the pieces back together. The recreated Agecroft Hall now stands in a setting similar to its original one on the banks of the Irwell River in Lancashire.” (Decoteau 1).

Most people always think about moving their house with them when they move to a different city and Williams did exactly that. He now had the property he purchased in Richmond with him. “Williams, who had earned his fortune in tobacco and as an investment banker, owned multiple acres of land in Richmond, on which his dream was to create an English village, called Windsor Farms, reminiscent of those he’d seen in England. (Visit Agecroft 1)

“He had no intention of replicating Agecroft Hall as it had stood in Lancashire. Instead, Williams salvaged sixteenth-century materials--timbers, window casements, paneling, leaded glass, door frames, the stone roof and the courtyard gates--and combined them with twentieth-century conveniences.” (Elvgren 1) It has been reported and researched that Williams spend about $250,000 to reconstruct this historical estate.

Sadly, Thomas C. Williams Jr. passed away not too long after Agecroft Hall was brought to Richmond in 1929. He was about to live in Agecroft Hall for about a year after its 2-2 ½ year reconstruction period was over. Marion Elizabeth Booker, Williams’ wife, continued to live at the estate for years to come. She remarried years later to a man named David Morton and continued to live in Agecroft hall until 1969.

It has been said that in Williams’ will, he said that he wanted Agecroft to turned into a museum after his wife either died or moved out of the estate. In 1969, that is exactly what happened. Years after his wife remarried, their former home was turned into a museum for all to visit.

Once you step inside of the reconstructed Agecroft Hall turned museum, you will instantly feel like you are back in the Tudor years in England. The museum does a fantastic job of keeping the estate looking as the Langley and Dauntesey would have lived.

When it was located in England, Agecroft Hall was a very large estate. “Today, the house is similar in style to the original building in England, but different in configuration. The original building was a quadrangular structure surrounding a central courtyard. However, there were many parts of the house that were not viable, so Agecroft today is only one-third the size that it was in England.” (Decoteau 1)

One of the most remarkable rooms in Agecroft Hall is the Great Hall. This room was primarily used for gatherings, business, entertaining guests, meals and for other various activities. Being the Great Hall is the room that most guests of the residents’ would enter through first, there are several lavish items in this room. One entire wall in the Great Hall is made of glass that serves as a window into the front of the house. This glass window is one of the first extravagant items that guests would see.

“An expansive 10 foot by 30 foot window that was original to the house and was shipped complete from England. Glass was expensive in the period, so a window as large as this was a clear sign of the importance and prosperity of the family. The Langley family installed the window and the Daunteseys added their coat of arms later.” (Decoteau 1)

Another great feature of Agecroft Hall are the magnificent gardens. Agecroft Hall sits on about plenty of acres, thus the space to create several beautiful gardens. The Williams’ hired a talented landscaper by the name of Charles Gillette to construct the stunning gardens at Agecroft Hall and that is exactly what he did. The gardens are filled with a variety of flowers, herbs and plants that all help in creating a warm and romantic feeling.

There are several different sections of the gardens that all join together to create one spectacular garden. It is interesting to realize that Agecroft Hall was once standing on the Irwell River in Lancashire and now is standing on the James River of Richmond. The view of the James River from the estate’s gardens and from some rooms is truly beautiful. That is just one example of how magical Agecroft Hall really is.

There are several rooms in Agecroft Hall that look very similar to how they would have looked in the earlier Tudor years. The Agecroft Hall museum staff takes pride in occasionally changing the “objects in the rooms to reflect the changes in seasons. The Dining Parlor and Great Parlor are also used to display plaster reproductions of foods representative of the diet of the period. Sometimes dancing or musical performances take place in them as well. In the summer, The Richmond Shakespeare Encore Group performs the Bard’s plays outside in the courtyard.” (Decoteau 1)

Several of the bedrooms in Agecroft Hall still have original 15th and 16th century furniture in them. For example, one of the bedrooms in the estate have an original 16th century complete bed frame set that still has its original paint covering it. This bed was painted in bright colors that were very unusual during this time, making it a priceless item the estate holds on to. This rare bed frame set also tells a story within the carvings. The carvings and decorations are meant to improve the chances of creating a child. This was a common task for the English because the family name was always wanted to carry on. By having children, families would insure that their legacy would not end.

Agecroft Hall also has a number of other original items such as large tapestries, original swords and armor, furniture, books and much more. This museum has kept and provided items to show that have been around for centuries.

The only room in Agecroft Hall that was not redecorated to resemble the Tudor period in England is the estate’s library. The library was never changed from the time with the Williams lived there. This room still has all of the Williams’ books, magazines and original furniture. The library is one of the largest rooms in Agecroft; it takes up one entire wing, and one of the most used rooms. By leaving this room untouched while the rest of the house was being transformed into the Tudor era, a piece of the Williams family will always be a part of Agecroft Hall.

Agecroft Hall is open all year round to entertain visitors that wish to learn more about the Tudor period of England. (Tuesday-Saturday 10am-4pm and Sundays 12:30pm-5pm). While visiting Agecroft Hall, not only will visitors be given a guided tour of the estate and gardens, but they will also be shown an informative video. This video explains the background history of Agecroft Hall and its significance to history today. A small fee will be charged per visitor, however it is a small price to pay to be exposed to all of the history of this estate and of the Tudor period. This historic estate is located at 4305 Sulgrave Road Richmond, VA 23221. Please visit http://www.agecrofthall.com/information.html to learn more information about this historical Tudor estate and how to plan your visit! Or call 804-353-4241.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Elvgren, Jennifer. "To be in England." Historic Traveler 4, no. 1 (November 1997): 58. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed November 26, 2011).

- "Agecroft Hall." Accessed November 26, 2011. www.agecrofthall.com.

- Virginia Tourism, "Agecroft Hall-Richmond, Virginia." Last modified 2001. Accessed November 26, 2011. http://www.virginiabeautiful.com/v4/agecroft-hall-richmond-virginia.html.

- Museum USA, "Agecroft Hall." Last modified 2011. Accessed November 26, 2011. http://www.museumsusa.org/museums/info/10511.

- Waddelove, Anna. Richmond.com, "A Piece of england, on the James." Last modified October 12, 2011. Accessed November 26, 2011. http://www2.richmond.com/lifestyles/discover-richmond/2011/oct/12/piece-england-james-ar-1338481/.

- Hanson, Marilee. Englishhistory.net, "Tudor England FAQ." Last modified 2004. Accessed November 26, 2011. http://englishhistory.net/tudor/faq.html.

- The British Monarchy, "History of the Monarchy." Last modified 2011. Accessed November 26, 2011. http://www.royal.gov.uk/HistoryoftheMonarchy/KingsandQueensofEngland/TheTudors/HenryVII.aspx.

- "The Protestant Reformation." Accessed November 26, 2011. http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1136.html.

- New England Antiques Journal, "Agecroft Hall & Gardens: Richmond's Remarkable Tudor Estate." Accessed November 26, 2011. http://www.antiquesjournal.com/pages04/Monthly_pages/dec06/agecroft.html .

- Info Barrel, "Visit Agecroft Hall: Richmond, Virginia." Last modified 2011. Accessed November 26, 2011. http://www.infobarrel.com/Visit_Agecroft_Hall__Richmond_Virginia.

- "The Agecroft Collection F.3.11-11." Accessed November 26, 2011. www.chethams.org.uk/chethams_library_agecroft_collection.pdf.

*Pictures of Agecroft Hall original work of Muna Futur

*Picture of Henry VII from http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/tudor.htm

*Picture of Henry VIII from http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/henry_viii.htm

*Picture of The Protestant Reformation from

Gothic Architecture in England

Present in England from c.1050-1650 (photographed example, Westminster Abbey: constructed (c.1050-1090, additions made until 1745)

Located across the British Isles (photographed example, Westminster Abbey: located in Westminster, UK)

England is a realm well known to be a land rich in architectural treasures spanning from the Neolithic period (i.e. the illustrious Stonehenge in Wiltshire) to the progressive “green” skyscrapers of glass, steel, and concrete arising today from the City of London, the heart of UK business. The country is an assortment of differing architectural styles which changed and evolved throughout this long history. Westminster Abbey (pictured) has been deemed a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of the nation’s most prized cultural and architectural possessions and is a prominent example of the Gothic style popular in the Middle Ages through to the early Tudor period and which continued to be constructed until the early Stewart period.

History

GENESIS OF THE STYLE

The term “Gothic” was applied to this architecture style and culture by those who invented it to mean barbarous due to its status as non-classical. The style found its inception in France, specifically in Burgundy and Provence as a development from earlier styles of Western Christian architecture (labeled “Classical” or “Romanesque” (Bond 7)). The earlier and more classical styles of building took root from Ancient Greek and Roman architectural schools and featured grand spaces characterized by high, sweeping domes like that of the Pantheon in Rome and columns for support.

The construction of Romanesque churches or “basilicas,” however, was often hampered by a particularly difficult problem. “Romanesque architecture is the art of vaulting a basilica…with nave, aisle walls, lean-to roof, and clerestory wall containing windows. This was the problem of problems for Western builders from the ninth century onward; to vault an aisled church without destroying its clerestory lighting” (6). Structurally, this paved the way for stylistic alterations to solve this problem. One solution was what would become Gothic architecture.

This new school of building was essentially a fusion of several main elements: of diagonal ribs, pointed arches, and flying buttresses, which culminated in an extremely unique and recognizable style which commanded attention.

` These sharp, dynamic features which dutifully served a very practical and structural purpose also left congregations in awe and wonderment and the Gothic style spread out of France and across Europe Prolifically “In fits and starts, [the spread of Gothic architecture] continued for the next four hundred years throughout Europe. By the mid-fifteenth century, Gothic cathedrals could be found from Scandinavia in the north to the Iberian Peninsula in the south, and from Wales in the west to the far reaches of Eastern Europe” (Scott 11).

Gothic Architecture continued to progress in England and the thirteenth century led to the rise of the “Decorated English Style” around the reign of Edward the First. This new design featured heavy ornamentation which became almost omnipresent. Ornate designs could be found present wherever one looked, to the grand facades on the outside, to the smallest intricate details found on individual wall brackets.

Gothic Architecture continued to progress in England and the thirteenth century led to the rise of the “Decorated English Style” around the reign of Edward the First. This new design featured heavy ornamentation which became almost omnipresent. Ornate designs could be found present wherever one looked, to the grand facades on the outside, to the smallest intricate details found on individual wall brackets.

Toker, Franklin. “Gothic Architecture by Remote Control:

An illustrated BuildingContract of 1340.” Art, Bulletin 67, no.1 (March 1985):67. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed November 27, 2011)

IMAGES IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE

Westminster Abbey. Taken by author

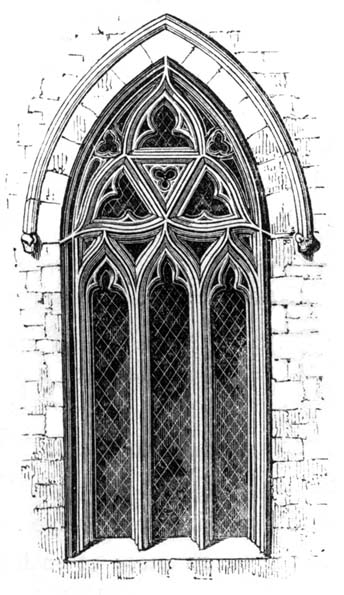

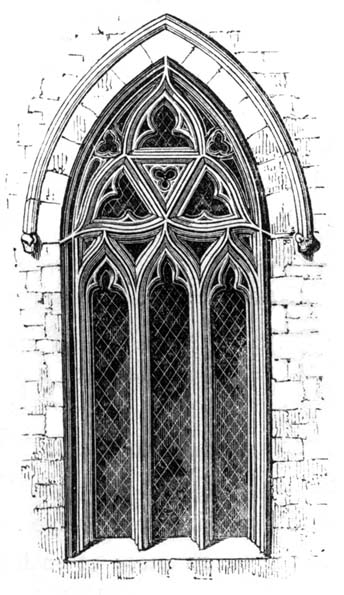

Window, Dunchurch Church, Warwickshire. Taken from The Principles of Gothic Ecclesiastical Architecture, Elucidated by Question and Answer, 4th ed

THE SPREAD TO ENGLAND

Romanesque/proto-Gothic structures were present in England before the Norman conquest of 1066, with the beginning of the construction of the first portion of Westminster Abbey in 1050 (Bond 14), however, with the advent of William the Conqueror’s invasion the land experienced a profound level of construction of churches in this style. “There was hardly one of the greater Anglo-Saxon churches which was not rebuilt and a great number of churches, entirely new, were erected” (Bond 14). This is a prime example of an immediate and long-lasting effect that the Norman Conquest of Britain had. Many of these places of worship were also grand in scale; much larger than their counterparts in the mother country. These are impressive facts, however, they are underscored even more by the fact that the entire land had a population of about half that of London in the present day (around four million).

The Romanesque/proto-Gothic explosion would continue in England for over a century, developing its own characteristics unique to the British Isles. Late in the 12th Century and early in the 13th century, however, the style transitioned into a fully Gothic model, starting with the larger cathedrals and buildings being constructed at the time, then filtering down to the smaller parishes and counties later on in the period.

FLOURISHING IN ENGLAND

Quite analogous to Darwin’s theory of Natural Selection and chance variation, as Gothic architecture evolved on the isolated island of Great Britain, English Gothic style differed from its continental counterpart. This led to a sense of “British-ness” and proto-national pride within the realm of England.

England | Length (ft) | Continent | Length (ft) |

Old St. Paul’s | 586 | Milan | 475 |

Winchester | 530 | Florence | 475 |

St. Albans | 520 | Amiens | 435 |

The table above indicates the emphasis on structural length of English Gothic cathedrals relative to continental cathedrals (Bond 49).

England | Internal Height (ft) | Continent | Internal Height (ft) |

Old St. Paul’s | 103 | Cologne | 155 |

Westminster | 103 | Beauvais | 150 |

York Choir | 102 | Bologna, S. Petronio | 150 |

The above table shows that English cathedrals fell short of those on the continent n internal height (Bond 50).

England | Area (sq. ft) | Continent | Length (sq. ft) |

Old St. Paul’s | 72,460 | Seville | 150,000 |

York | 63,800 | Milan | 92,600 |

Lincoln | 57,200 | Saragossa | 80,000 |

The continental cathedrals also were superior in area (Bond 50).

The specific “Anglo-Norman” style of truly Gothic architecture can trace its development to the reign of Edward the Confessor. His construction of what is now Westminster Abbey heralded truly the breakaway design which is deemed worthy of its own category (Bloxam). This style may be recognized by its semicircular arches, its massive piers, which are generally square or cylindrical, and from numerous ornamental details and moldings which are specific to the style.

Gothic Architecture continued to progress in England and the thirteenth century led to the rise of the “Decorated English Style” around the reign of Edward the First. This new design featured heavy ornamentation which became almost omnipresent. Ornate designs could be found present wherever one looked, to the grand facades on the outside, to the smallest intricate details found on individual wall brackets.

Gothic Architecture continued to progress in England and the thirteenth century led to the rise of the “Decorated English Style” around the reign of Edward the First. This new design featured heavy ornamentation which became almost omnipresent. Ornate designs could be found present wherever one looked, to the grand facades on the outside, to the smallest intricate details found on individual wall brackets.Decorated English Style prevailed throughout the next century and was followed by developments during the reign of Edward the Third (c.1375) which can be grouped and referred to as “Perpendicular (or Florid) English Style” (Bloxam). Like the preceding style, the Florid or Perpendicular style was heavy in ornamentation, however, it differed in that the “beautiful, flowing contours” of the Decorated style were superseded by direct vertical and horizontal lines of division and angular edges (Bloxam). This style, enjoying prominence until the middle of the sixteenth century may also be seen as the climax or turning point in the history of Gothic architecture in England.

It was after roughly a century and-a-half of the predominance of the Perpendicular style within the British Isles that the final incarnation of the English Gothic form of architecture took hold. This form, known as the “Debased Style” was, nevertheless far inferior in design compared to its illustrious and ornate predecessors. Emerging into existence around 1540 in the later years of the distinguished reign of Henry VIII, Debased style was stylistically more simple and inauspicious. The name “Debased” itself arises from “the general inferiority of design compared with the style it succeeded, from the meagre and clumsy execution of sculptured and other ornamental work, from the intermixture of detail founded on an entirely different school of art, and the consequent subversion of the purity of style” (Bloxam). As explored below in the “Gothic Architecture and the Reformation” section of this entry, the decline of the Gothic style in England is closely linked to the changed brought about by Henry during the Protestant Reformation.

Though the art and construction of the Gothic style fell into decline at about this time, a revival of interest and intrigue into the art of Gothic architecture took off in England around two centuries later in the 18th and 19th centuries. This “Gothic Revival” style, as it is known, spread throughout Europe and into North America well into the 20th century.

Stylistic features

Though Gothic style within England progressed, changed, evolved, and devolved within the course of around six centuries, as enumerated above, English Gothic style can be described generally as, in essence, a culmination or fusion of several key elements. These elements were mainly a result of the constructional challenges to the erection of churches that the Romanesque and Classical styles posed to architects and builders. Plainly, the major characteristics shared by buildings constructed in the English Gothic style are pointed arches, diagonal ribs, and flying buttresses.

· Pointed Arches: Perhaps the most noticeable exterior feature of Gothic cathedrals and other structures is the pointed arch. Though there are a myriad of different types of pointed arches that have been employed in Gothic construction (such as the “obtuse” and “Tudor” arches), pointed arches can be found on any surviving Gothic cathedral. The vault of Gothic cathedrals is impossible without this shape and it is, therefore, ubiquitous and essential to the structure. (Toker 187)

· Diagonal Ribs: Similar in shape to the pointed arches, these diagonal ribs were used on the ceilings of Gothic cathedrals, generally above the aisles. Like the pointed arch, its shape is essential to vaulting the structure. (Toker 190)

· Flying Buttresses: This exterior design feature encompasses the angular shape of both the pointed arch and diagonal rib. The primary purpose of the flying buttress was to support the exterior facades of the structure.

Gothic Architecture and the Reformation

Henry’s Reformation of the Church and the establishment of Anglican Church, of which he appointed himself the premier, unintentionally and quite accidentally had profound implications for the history of Gothic Architecture, specifically its downfall. On the eve of this unprecedented and immense religious, social and political change, England’s landscape was unparalleled in the number of religious edifices of sheer variety of style collected across the ages. “Next to the magnificent cathedrals, the venerable monasteries and collegiate establishments, which had been founded and sumptuously endowed in every part of the kingdom, might most justly claim the preeminence; and many of the churches belonging to them were deservedly held in admiration for their grandeur and architectural elegance of design” (Bloxam).

Perhaps the largest contributing factor to the downfall of this most interesting school of architecture which had endured for so long was the dissolution of the monasteries. The responsibility of building, rebuilding, and decorating the existing monasteries which had been built over the course of several centuries (which often proved costly with such lofty and intricate designs) had been defrayed out of the monastic revenues and private donations historically. However, when the crown seized these, the construction and upkeep of these historically precious facilities declined and many fell into ruin (Bloxam).

Much of the Protestant and Puritan contempt toward the Catholic Church lay in its emphasis on ornamentation. Gothic style, as detailed earlier, is characterized by an extreme attention to detail and contained ubiquitous elaborations (Farahbakhsh 184). As the Protestant wave became dominant within the country, reformers, in addition to cutting down on the ornamental practices and rituals of the Church, also curbed any further excessive decoration on new churches. Additionally, as the older structures crumbled, they were renovated in less stylistic fashion. “Parochial churches were, therefore, now repaired when fallen into a state of dilapidation, in a plain and inelegant mode, in complete variance with the richness and display observable in the style just preceding this event” (Bloxam).

In the stead of the Gothic style, more classical design originating from Italy began to predominate during the 16th century and by the reign of Charles I little remained of the Gothic.

Bibliography

Bloxam, Matthew. The Principles of Gothic Ecclesiastical Architecture, Elucidated by Question and Answer, 4th ed.. Oxford, UK: 2006. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/19737/19737-h/19737-h.htm

Bond, Francis. Gothic Architecture in England. Hallandale, FL: New World Book Manufacturing Company, 1972.

Farahbakhsh, Alireza. "Social Protest Through Architecture: Ruskin's "The Nature of Gothic" as an Embodiment of His Artistic and Social Views." Midwest Quarterly 52, no. 2 (Winter2011 2011): 182-199. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed November 28, 2011).

Hawkins, John. An History of the Origin and Establishment of Gothic. London, UK: S. Gosnel, http://books.google.com/books?id=iKAaAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=gothic architecture history&hl=en&ei=j43RToWcIcLg0gGfoNn0Dw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDoQ6AEwAQ

Scott, Robert. The Gothic Enterprise: A Guide to Understanding the Medieval Cathedral. London, UK: University of California Press, 2005.

Toker, Franklin. “Gothic Architecture by Remote Control:

An illustrated BuildingContract of 1340.” Art, Bulletin 67, no.1 (March 1985):67. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed November 27, 2011)

IMAGES IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE

Westminster Abbey. Taken by author

Window, Dunchurch Church, Warwickshire. Taken from The Principles of Gothic Ecclesiastical Architecture, Elucidated by Question and Answer, 4th ed

An Embroidered Portrait of King Charles I

by Rebecca Hackett

Made in England, ca. 1645

Located in Agecroft Hall, Richmond, VA

This miniature portrait of King Charles the First, who reigned from 1625 to 1649, is a masterwork of delicate and naturalistic embroidery. Charles is depicted in a red doublet with a falling band of white lace and (presumably) a medallion on a thick blue silk ribbon hung around his neck. His brown hair appears soft and natural, his upturned moustache and pointed “Van Dyck” beard reflective of the King’s customary appearance and the style of the day. His expression is saint-like and contemplative. The background is of a green that contrasts nicely with the red of his doublet. Encircling the serene image of Charles is a border, also of embroidery, that seems to have a series of small sequins appliquéd into it. The whole item is housed in an oval frame made of metal with a loop at the top in order for the image to be suspended from a ribbon or chain for display.

A similar miniature depicting Charles resides in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The same reference image was very obviously used for both portraits, as the King is depicted in the same position and attitude in each. According to the description of the MET miniature in the exhibition catalog, the images are both based on a series of engravings by Wenceslaus Hollar in the 1640s, which are based in turn on the many portraits of King Charles by Anthony Van Dyck (Watt 116). The MET miniature is more vivid in coloration (the Agecroft miniature has faded or been otherwise worn over the centuries) and shows more of Charles’ figure, as well as displaying a motto embroidered over the top of the image. The motto is a quotation from the Psalms and associates Charles with the Biblical King David, referencing both Charles’ divine right as ruler of England and his sainthood as recognized by the Church of England upon his execution in January of 1649 (Watt 118).

According to the MET, these miniatures of the deceased martyred King were intended not to be worn, like other miniatures of the day, but rather displayed in a cabinet or upon a wall. A 1650 portrait of contemporary playwright Thomas Killigrew by William Shephard depicts the playwright seated with a similar, if not identical, picture of Charles on the wall behind him. The image of the King is included as an attribute to Killigrew, defiantly showing his continued Royalism and loyalty to the Stuart line even after the Parliamentarians had come to power and poor King Charles had been beheaded. This painting shows how such miniatures of the deposed King would have been utilized by the people of the time. Despite intense antagonism by the Republican Roundheads to any and all shows of Royalist support (or any opposition to their militaristic rule), it seems that such displays of loyalty were not uncommon, especially since “no serious attempt seems to have been made to prevent the display of the King’s portrait in private houses” (Tavares).

PRODUCTION AND TECHNIQUE

Most fine embroidered works, such as this miniature and other, larger works of art, were crafted by professional embroiderers within guilds (Brooks 10). These people were men who had been extensively trained in the art in order to maintain a high standard of production associated with the guild’s work. A similar process of educating embroiderers is continued today in England’s Royal School of Needlework, which was founded in the 1870s, although the student body largely consists of women (RSN History).

Other works were created by the daughters of the wealthy, who saw such “curious” work as beneficial to display the girl’s talents and to fill her idle hours, instead of the Latin and rhetoric learned by her brothers. Many young women were able to produce embroidered work similar or equal in quality to that of the guildsmen’s. These young ladies were often educated on a large scale in schools such as the one at Hackney Church, located just outside of London and called colloquially “The Ladies University of the Female Arts.” According to Brooks, over 800 girls were educated in needlework at the Hackney School during the span of years between the Civil War and the Commonwealth alone (11).

Despite the strictly regimented teaching of embroidery both in guilds and in schools of “female arts,” ingenuity seems to have been particularly valued by seventeenth-century embroiderers. Names of stitches changed frequently over the years as well as popular techniques. As one rather accomplished young lady bragged in the 1660s: “I never was taught one stitch and most what I do now is all from my own fancy” (Brooks 22). The subjects of the embroideries also reflect this ingenuity, as even biblical scenes were often populated with mermaids, unicorns, and other fantastic creatures.

Popular motifs for embroidered scenes were animals, flowers, and biblical tableaux. Many of the pictures from this period have hidden meanings or images, often in support of English monarchy or in commemoration and sympathy for Charles I’s execution. Caterpillars and butterflies are often interpreted as representing, respectively, Charles I and the Restoration (Brooks 14). In one post-1634 embroidered portrait, Charles I and his wife Henrietta Maria are shown alongside Adam and Eve, with the royal couple’s pose and physical appearance mirroring that of the biblical first couple. The juxtaposition of the subjects is meant to trace Charles’ God-given right as ruler all the way back to before the Fall, an interpretation that was favored by Royalists, who viewed Adamic patriarchy as the basis of Divine Right of kings (Watt 122). Depictions of the story of Moses seem to have a link to Charles II, who was seen as a Moses-like figure who “delivered his people through the restoration of the monarchy,” although this interpretation of deliverance could also pertain to Cromwell and the Parliamentarians, who had delivered the people from the monarchy (Brooks 15).

CIVIL WAR AND EXECUTION

Charles I was not a popular monarch, but even after two bouts of Civil War in England, no one expected that he would find himself on the executioner’s block. His reign was quite controversial because of both political and religious matters.

Politically, Charles believed in the Divine Right of Kings. He felt he had no need for Parliament unless they were serving his needs and ideals, a belief that would lead to his dismissal of Parliament for over ten years of his reign: from 1629-1640. Although he was entirely within his rights to refuse to call a Parliament, many of the people of England disagreed. Charles’ desperate needs for funds caused him to exploit loopholes in English law, scouring old medieval documents for lapsed laws that could gather some revenue. Some of these exploitations were more palatable than others, such as his practice of rewarding his allies with trade monopolies, but others, such as the “ship money,” became a huge source of tension and ill feelings toward Charles as a monarch. Originally written during medieval times to help protect the coasts of England, the ship money law stated that coastal towns were required to provide a certain number of ships. Charles reinstated this law, only allowed the towns the option to send him cash instead (Daems 42). At first it seemed all would be well, since the law seemed to make sense. However, as Charles demanded ship money from towns further and further inland, it became clear that he was simply using them to fill the depleted royal coffers.

Religiously, Charles was a lover of music and ceremony during his church services. Born and raised a Protestant (the first monarch to be raised thus), Charles did not wish for the Anglican Church to revert back to Catholicism, but the staunchly Puritan sects within his congregation did not trust him, especially since his beautiful French wife, Henrietta Maria, was a practicing Catholic who was permitted to practice her religion within the confines of her private chapel (Watt 66). William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, was also an advocate for the restoration of pomp and circumstance to the Anglican services. With the power of the Court of High Commission and the Star Chamber, Laud and Charles began to strip the Puritan elements from the Anglican church: clergymen who voiced Puritan sympathies would be dismissed, vestments would be made mandatory, and imposition of a new Book of Common Prayer on largely Presbyterian Scotland. These measures frightened many of the more conservative Puritan Englishmen, who worried that “Popery”, would return to England.

The Scots opposition to Charles’ promulgation of Anglicanism within Scotland led to, in 1640, the Bishop’s War, a Scottish invasion of England that had Charles even more badly in need of money than before. He called Parliament, hoping that his previous difficulties with them would have dissipated in the long years since they had last been in session. This would not, however, be the case, since House of Commons leader John Pym had strong Puritan sensibilities and sympathized with the Scottish plight. In three weeks, nothing had been accomplished and King Charles dissolved Parliament, determined to raise an army without the assistance of Parliament.

The Scots opposition to Charles’ promulgation of Anglicanism within Scotland led to, in 1640, the Bishop’s War, a Scottish invasion of England that had Charles even more badly in need of money than before. He called Parliament, hoping that his previous difficulties with them would have dissipated in the long years since they had last been in session. This would not, however, be the case, since House of Commons leader John Pym had strong Puritan sensibilities and sympathized with the Scottish plight. In three weeks, nothing had been accomplished and King Charles dissolved Parliament, determined to raise an army without the assistance of Parliament.Charles went to war against the invading Scots, but his forces were quickly defeated. A tentative peace was reached, but all the power was left firmly in the hands of the Scots, who were permitted to continue their occupation of English soil with all their expenses paid until the church question was at last settled.

Reluctantly, Charles had to call Parliament into session again, the second time that year. This Parliament, which would last until 1660, would be called the Long Parliament. Charles, badly in need of Parliamentary funding and assistance especially after his rather embarrassing defeat, was forced to stand by as the long-ignored MPs began proceedings to reduce the power of the King. Many of Charles’ supporters were attainted and executed, including William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury. Parliament also made it illegal for the King to dissolve Parliament and demanded it be convened at least every three years. Ship money was abolished, as were the Star Chamber and Court of High Commission. Charles’ absolute reign was at an end.

As if all this humiliation at the hands of Parliament and the Scots was not enough, the Irish, no longer able to bear the yoke of the plantation system, rebelled. The Irish, even in the seventeenth century staunchly Catholic and firmly against Protestantism, drove ten thousand English plantationers off their land, stripped them of clothing and property, and drove them naked into the wilderness. Ordinarily, a drastic and terrifying rebellion such as this one might have driven Parliament and the King into an alliance. This time, however, the Parliament’s mistrust of the King and their fear of Catholicism ran too deeply. The rebellion was magnified by the London Press, and the fear of Catholicism grew stronger.

In 1642, with his power fading and Parliament firmly set in their ways against him, Charles stormed the Parliamentary chambers in order to arrest several MPs who were suspected of collusion with the Scots of the Bishop’s War. His attempt failed, as the MPs had been warned beforehand of his impending attack. With this one foolish move, Charles lost the last shreds of remaining support and was forced to flee London. Now, both sides began to arm themselves: the Civil War had begun.

Parliament allied itself with the Scottish Covenanters who had so recently invaded, on the condition that the Scots would be paid and that Presbyterianism be taken up in England after the war was won. Parliament also raised a “New Model Army”, small in size but heavily disciplined. Charles allied himself with the Irish Catholics, a move which lost him further support from those who demonized Catholics. Despite having the Irish on his side, Charles was still defeated by the Parliamentary forces. In 1646, a truce was declared. Charles, in the hands of the Scots, was transferred to the custody of the Parliamentarians (Corns 60).

Even at this late date, it seemed impossible that Charles would be executed. The Moderates within Parliament wanted to decommission the New Model Army and put Charles back on the throne, albeit within the confines of the new laws instated by the Long Parliament before the Civil War. The Radicals, however, especially the Levellers, a small group of extreme radicals, wanted a huge change to occur: there would be a republic, with absolute sovereignty of the people, as well as social equality, total religious toleration (except for Catholics), manhood suffrage, and an end to monarchy in England. These Levellers, though small in number within Parliament, were strong within the New Model Army. When the moderate Parliament moved to disband the army with no back pay, war broke out once again. Now Parliament itself was divided.

Even at this late date, it seemed impossible that Charles would be executed. The Moderates within Parliament wanted to decommission the New Model Army and put Charles back on the throne, albeit within the confines of the new laws instated by the Long Parliament before the Civil War. The Radicals, however, especially the Levellers, a small group of extreme radicals, wanted a huge change to occur: there would be a republic, with absolute sovereignty of the people, as well as social equality, total religious toleration (except for Catholics), manhood suffrage, and an end to monarchy in England. These Levellers, though small in number within Parliament, were strong within the New Model Army. When the moderate Parliament moved to disband the army with no back pay, war broke out once again. Now Parliament itself was divided.The Army, led by Oliver Cromwell, routed the Parliamentary forces. Military rule was instated. Negotiations about what would happen to the King were silenced. Monarchist MPs were purged from the seats of Parliament. The 50 radical MPs who were left put Charles on trial in January 1649 for high treason.

CANONIZATION AND THE CULT OF THE ROYAL MARTYR

During the Restoration in 1660, Charles was elevated to the status of Martyr. Yearly on the anniversary of Charles I’s death, congregations would gather to hear sermons and prayers asking for forgiveness from God for the sin of regicide. He, King Charles the Martyr, is the only saint officially canonized within the Anglican church.

A book was published almost immediately after Charles’ death, purporting to be his last thoughts and prayers. This was the Eikon Basilike, which became extremely popular and contributed immensely to his portrayal as a “Christ-like martyr king” (Watt 69). The Scots who sold him into the hands of Parliament were labeled Judas, traitors not only to King and country but to their brother Scotsman (Corns 60). The Christ-like image of a lonely king, forsaken by his family who had been forced to flee the country, and forsaken further by his subjects who had murdered him, was an amazing piece of Royalist propaganda. More than thirty-five English language editions of the book were published in 1649, the same year of Charles’ death, and more editions in languages such as Latin and Dutch would quickly follow (Corns 122).

A book was published almost immediately after Charles’ death, purporting to be his last thoughts and prayers. This was the Eikon Basilike, which became extremely popular and contributed immensely to his portrayal as a “Christ-like martyr king” (Watt 69). The Scots who sold him into the hands of Parliament were labeled Judas, traitors not only to King and country but to their brother Scotsman (Corns 60). The Christ-like image of a lonely king, forsaken by his family who had been forced to flee the country, and forsaken further by his subjects who had murdered him, was an amazing piece of Royalist propaganda. More than thirty-five English language editions of the book were published in 1649, the same year of Charles’ death, and more editions in languages such as Latin and Dutch would quickly follow (Corns 122).Charles’ last words were “I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible crown” (Daems 323). These words, taken from Corinthians 9:25, suggest a movement from the state of humanity to the state of divinity; not just a transfer of the immortal soul from Earth to Heaven, but a change in its very essence (Carrol 214). This moment, immortalized in the Eikon Basilike, further contributed to his saint-like image in the minds of the Royalists. The embroidered miniatures depicting a gentle and saint-like Charles with his eyes raised pensively heavenward were now to be created in a great quantity by professional embroiderers for sale to the growing Cult of the Royal Martyr, which would remain popular even into the eighteenth century (Watt 69).

"By decapitating Charles I, Parliament...created a myth which covered all the flaws in the king and revealed only the virtuous martyr" (Stewart 175). The ensuing Cult of the Royal Martyr built itself up around the anniversary sermons preached yearly on Charles' death date. Not only did the cult practice religious veneration, but the continued observation and discussion of Charles' execution served as a cautionary tale for extremists on both the royalist side as well as the republican (Stewart 175).

Even through the reign of Anne, who reigned from 1702 to 1707, the Cult of the Royal Martyr continued to revere the sacred personality of Charles I. By this time, the worship of the Stuart King had gathered somewhat of an unsavory reputation (Stewart 185). The Glorious Revolution, where again a King was overthrown (no beheading and martyrdom this time, only forced abdication), made the House of Orange the legitimate rulers of England and called the Stuart line mere pretenders. Jacobites, as the supporters of the overthrown King James II were called, could be tried for treason. As the Cult of the Royal Martyr venerates the father of this King, it is easy to see how the Cult could have become attainted. After this point, the popularity of the Cult waned into obscurity and the observation of the anniversary of his death as written into the Anglican Book of Common Prayer was eventually removed by Queen Victoria (r. 1837-1901).

"By decapitating Charles I, Parliament...created a myth which covered all the flaws in the king and revealed only the virtuous martyr" (Stewart 175). The ensuing Cult of the Royal Martyr built itself up around the anniversary sermons preached yearly on Charles' death date. Not only did the cult practice religious veneration, but the continued observation and discussion of Charles' execution served as a cautionary tale for extremists on both the royalist side as well as the republican (Stewart 175).

Even through the reign of Anne, who reigned from 1702 to 1707, the Cult of the Royal Martyr continued to revere the sacred personality of Charles I. By this time, the worship of the Stuart King had gathered somewhat of an unsavory reputation (Stewart 185). The Glorious Revolution, where again a King was overthrown (no beheading and martyrdom this time, only forced abdication), made the House of Orange the legitimate rulers of England and called the Stuart line mere pretenders. Jacobites, as the supporters of the overthrown King James II were called, could be tried for treason. As the Cult of the Royal Martyr venerates the father of this King, it is easy to see how the Cult could have become attainted. After this point, the popularity of the Cult waned into obscurity and the observation of the anniversary of his death as written into the Anglican Book of Common Prayer was eventually removed by Queen Victoria (r. 1837-1901).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brooks, Mary M. English Embroideries--16th & 17th C. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 2006.

Carrol, Robert, and Stephen Prickett, eds. The Bible: Authorized King James Version with Apocrypha. New York: Oxford World Classics, 1997.

Carrol, Robert, and Stephen Prickett, eds. The Bible: Authorized King James Version with Apocrypha. New York: Oxford World Classics, 1997.

Corns, Thomas N., ed. The Royal Image: Representations of Charles I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Daems, Jim, and Holly F. Nelson, eds. Eikon Basilike: The Portrait of His Sacred Majesty in His Solitudes and Sufferings: with selections from Eikonoklastes, John Milton. Sydney: Broadview Press Ltd, 2006. http://books.google.com/books?id=41qVuEh1MXwC&lpg=PA28&dq=Eikon%20Basilike%3A%20The%20Portrait%20of%20His%20Sacred%20Majesty%20in%20His%20Solitudes%20and%20Sufferings&pg=PA4#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Royal School of Needlework. "Royal School of Needlework History." http://www.royal-needlework.org.uk/content/13/royal_school_of_needlework_history.

Stewart, Byron S. "The Cult of the Royal Martyr." Church History 38, no. 2 (1969): 175-187. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3162705.

Tavares, Jonathan. "Embroidered Miniature of Charles I." Bard Graduate Center. http://www.bgc.bard.edu/gallery/gallery-at-bgc/past-exhibitions/past-exhibitions-embroidery/oom-twixt-miniature.html.

Watt, Melinda, and Andrew Morrall. English Embroidery in the Metropolitan Museum: 1575-1700: 'Twixt Art and Nature. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009.

IMAGES IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE

Embroidered Miniature of Charles I, artist unknown, 1640, located in Agecroft Hall, Richmond, US. Image taken from postcard.

Portrait of Thomas Killigrew, by William Shephard, 1650, located in National Portrait Gallery, London, UK. Image taken from Watt book.

Adam and Eve with Charles I and Henrietta Maria, artist unknown, post-1634, located in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, US. Image taken from Watt book.

John Pym, by Edward Bower, 1640, located in National Portrait Gallery, London, UK. Image taken from NPG Website.

Miniature of Oliver Cromwell, by Samuel Cooper, 1656, located in National Portrait Gallery, London, UK. Image taken from NPG Website.

Frontispiece of Reliquiae Sacrae Carolinae, post 1651, located in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, US. Image taken from Watt book.

Charles I, King of England, from Three Angles, 1636, located in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, UK. Image taken from Draw-Paint-Sculpt.

John Pym, by Edward Bower, 1640, located in National Portrait Gallery, London, UK. Image taken from NPG Website.

Miniature of Oliver Cromwell, by Samuel Cooper, 1656, located in National Portrait Gallery, London, UK. Image taken from NPG Website.

Frontispiece of Reliquiae Sacrae Carolinae, post 1651, located in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, US. Image taken from Watt book.

Charles I, King of England, from Three Angles, 1636, located in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle, UK. Image taken from Draw-Paint-Sculpt.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)